The Radium Girls – the dark history behind glowing dials

On the morning of April 10th, 1917, a young woman walks trough the doors of her new workplace in Orange, New Jersey, USA. She is giddy with excitement and beaming with pride of this new opportunity. Her new employer is the United States Radium Corporation, and she is Grace Fryer, a dial painter who will end up making history.

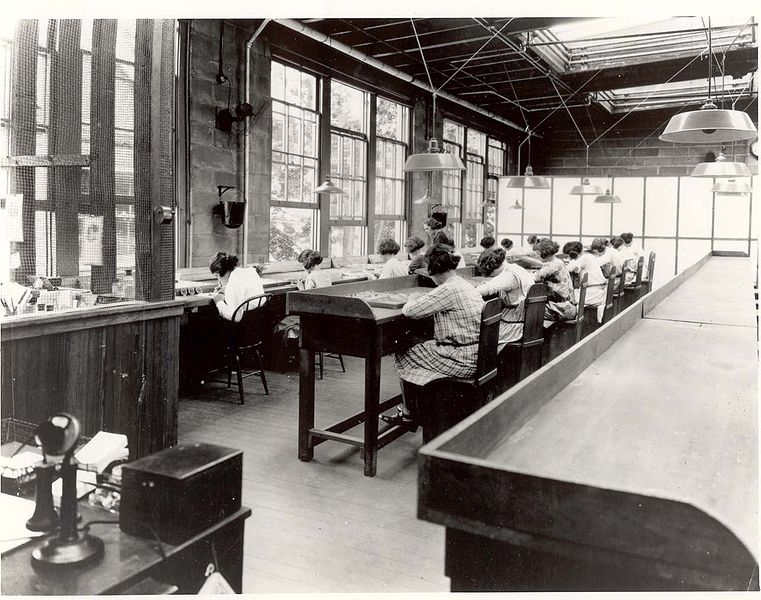

Working as a dial painter back in the early 1900’s was a job occupied solely by women, it was a prestigious job however and the women doing this work enjoyed not only high wages, but also serene working conditions in spacious and well lit offices. Not to mention the fact that many did the job to support the war effort of WW1. These attributes is not what history will take away from the story of the “Radium Girls” but rather corporate greed, indifference to worker health and great personal loss. The final outcome did however set history on a slightly better course and ensured worker health for future generations.

The discovery of radium by Marie Curie in 1898 sparked excitement across the scientific and medical communities. Radium’s luminescent properties and perceived therapeutic effects led to its use in various medical treatments. Radiologists and physicians used radium to treat conditions like cancer, arthritis, and even as a tonic for general health improvement.

In the early 1900s, radium’s luminescence made it particularly suitable for the production of self-luminous watch dials and instruments. Companies like the United States Radium Corporation and Radium Dial Company capitalized on this demand. They hired young women to become dial painters, responsible for meticulously applying radium-based paint to create glowing watch dials. These women included Grace Fryer, Katherine Schaub, Edna Hussman, Quinta McDonald, and Albina Larice, among others.

Grace and her colleagues, across the country, worked away paining dials happy about their safe, well-paying job that also did a civil service. To achieve a fine point on their brushes, they used a technique known as “lip-pointing”, or “lip-dip-paint-routine” as Melaniw Marnich, one of the raduim girls, described it. This involved moistening their brushes with their lips, resulting in the ingestion of small amounts of radium with each brushstroke. They had been told, explicitly, that this technique was safe, and that ingesting small amounts of radium was actually beneficial to your health. As was the belief at the time, and people even drank tonics of radium infused water, there was cosmetics, food and even toothpaste available at the time and believed to work wonders for your health. This general belief came from research funded by the companies using radium to sell product, and these companies readily ignored any warning sign that radium may be less beneficial than first imagined.

As time passed, some of the Radium Girls began to experience mysterious and debilitating health issues. Severe pain, anaemia, bone fractures, and jaw necrosis were among the symptoms they suffered. They were perplexed by their ailments, as the companies assured them that radium was harmless. One such girl was a colleague of Grace Fryer named Amelia Maggia. In 1922 Amelia fell ill and she quit the work at the USRC. What started as an aching tooth soon developed into something much more sinister. Her dentist pulled the aching tooth, but soon after other teeth started hurting, as these were pulled painful ulcers sprouted like morbid weeds in her jaw and mouth. Her doctors couldn’t tell what was wrong and prescribed her aspirin and sent her home. By mid-1922 she had gotten severely ill, and most of her teeth were gone and now her jawbone started falling apart as well. By September of 1922 Amelia “Mollie” Maggia succumbed to the radiation poisoning. She was 24.

By this time, many of Mollies colleagues were following in her tragic footsteps, and many of the dial painters started succumbing to severe illness and ultimately death caused by radiation.

As more and more fell ill and died, they sought more extensive medical help and were horrified to discover that radium was the cause of their suffering. The companies employing them, however, denied any connection between radium exposure and their health problems. The girls decided to take legal action.

In 1927, Radium Girls like Grace Fryer, Katherine Schaub, and Edna Hussman initiated lawsuits against their former employers. They sought compensation for their suffering and to hold the companies accountable for their negligence. The legal battles proved to be an uphill struggle, as the companies, backed by powerful lawyers, staunchly defended their actions. The companies even resorted to not only lying but also cover up and theft of bones to cover their tracks and deny any responsibility.

Despite facing challenges and fierce opposition, the Radium Girls’ fight for justice continued. The case of Grace Fryer and others finally went to trial in 1928. Their courageous testimonies, supported by compelling evidence, highlighted the hazards of radium exposure and the companies’ negligence. The verdict awarded Grace and her colleagues compensation for their suffering.

The Radium Girls’ lawsuits and the subsequent verdict garnered significant public outcry. The tragic plight of the Radium Girls brought attention to the urgent need for better workplace safety regulations. The government launched investigations into the health hazards of radium exposure, leading to the implementation of stronger regulations to protect workers.

The legacy of the Radium Girls lives on as a poignant reminder of the consequences of neglecting worker safety. Their sacrifice and determination paved the way for future generations, shaping labour laws and regulations to protect workers from hazardous substances and environments. Their fight and victory against the radium companies even led to the establishment of OSHA – Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a leader in worked health and safety even today. The Radium Girls’ fight for justice remains a symbol of the power of collective action and the importance of upholding workers’ rights.

The use of radium in various industries declined significantly in the decades that followed. The dangers of radium exposure were now widely known, leading to its disuse in many applications. The tragic story of the Radium Girls played a pivotal role in this shift, as society became more aware of the necessity to prioritize worker safety and health over profit.

In wristwatches radium was ultimately stopped in the 1970’s and replaced by other luminescent materials, such as Tritium and later SuperLuminova. If a watch is made prior to the early 70’s we’d recommend checking it with a Geiger counter as radium have a half-life of about 1600 years, meaning that it will be dangerous for quite some time still and thus continue to pose a danger to collectors of today.

Grace Fryer died in 1933, just 34 years old. Today, the Horological Society of New York (HSNY) award the “Grace Flyer Scholarship” to female watchmaking students, named after miss Fryer keeping part of her and the other “Radium Girls” legacy alive.